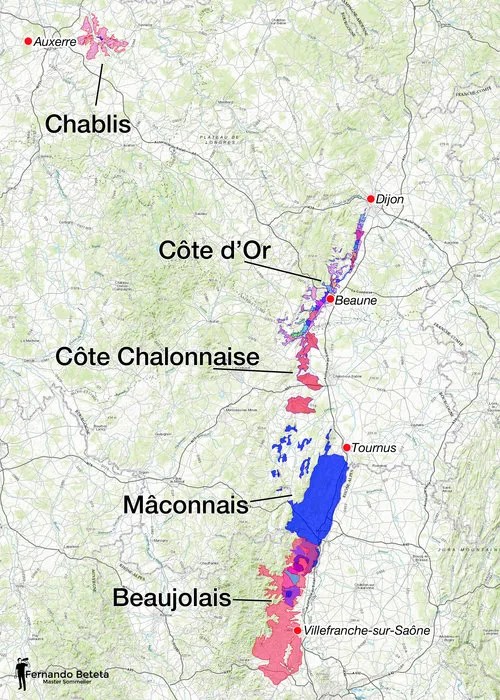

In a previous post, I explored potential Australian alternatives to Burgundian Chardonnay. This was in response to part one of a WSET Level 3 practice question. Before I move on to part two, which (spoiler alert) takes a deep dive into the wines of Bordeaux, I want to finish up my tour of Burgundy with a quick look at the regions not discussed in that prior post.

[Information based on WSET Level 3 material]

Chablis

Chablis is a village appellation (Learn more about The Hierarchy of Burgundy Appellations) and is the northern-most appellation in Burgundy. As you can see from the map below, the dominating geographical feature is the river Serein. The very best vineyards—the premiers crus and grand cru—lie mid-slope along the hills that face the river. Because Chablis’ climate is cool continental, it is in these locations that grapes can receive ample sunlight as well as warmth and reflection from the river and thus ripen to a depth and complexity unlike in either Petit Chablis or Chablis. Chablis premiers crus and grand cru Chardonnay is riper, contains more concentrated fruit flavors of citrus fruits, and have a fuller body (though still, overall, light-bodied)—all while maintaining a naturally high level of acidity. With fancy grapes comes fancy winemaking, and many producers investing in the use of old oak casks to create a rounder texture as well as add subtle flavors to the resulting wines. Note: Some winemakers, in an effort to promote the pure varietal flavors, will ferment and store their wines in inert vessels (concrete or stainless steel).

The other geologically defining feature are the soils. The soils here are limestone, Kimmeridgean limestone. This soil dates back nearly 150 million years ago, and is composed of rocks and stones that were deposited on an ancient seabed. This is inter-mixed with layers of marl: limestone clay that has been compressed into rock. Looking closely, one can often find fossils of oyster shells that date back to the Jurassic Period. This is why many describe the wines of Chablis as minerally, with notes of salinity—and why the wine goes just so well with oysters.

Petit Chablis are thought of as the “lesser vineyards,” and one can take that literally, as the vines are mostly planted along the valley floor. It is here where the risk of frost is enhanced, and grape growers often utilized the assistance of sprinklers or heaters to help protect the vines.

Côte d’Or

Please refer back to The Australian Alternative to French Favorites Part 1 for a detailed look into both the Côte de Nuits and the Côte de Beaune.

The Côte Chalonnaise

The vineyards of the Côte Chalonnaise are planted at a higher altitude, thus they are harvested later and ripening, unfortunately, is less reliable. Additionally, the aspect of these vineyards are “less consistently east.” Resulting wines are lighter, mature earlier, and are considered less prestigious than those form the Côte d’Or. There are four village appellations in the Côte Chalonnaise:

- Rully (produces both red and white)

- Mercurey (known best for red wines)

- Givry (known best for red wines)

- Montagny (produces only white wines)

FUN FACT: All of these villages have premier cru vineyards but no grands crus.

The regional appellation is Bourgogne Côte Chalonnaise.

Mâconnais

Here, Chardonnay is the most widely planted grape and FUN FACT: the reds are predominantly Gamay.

The regional appellation is Mâcon, referring to either red or white wine grown from any site in the region. Mâcon Villages (or Mâcon followed by the name of a specific village) refer specifically to white wines. These wines are very similar to the regional white wines, but may display more ripeness, body, and varietal character.

The two most famous Mâconnais village appellations are:

- Pouilly-Fuissé

- Saint-Veran

In these appellations, vines are planted on east and south-east-facing slopes filled with limestone soils. Furthermore, the slopes create an amphitheater-like shape that works to further trap the warmth and light of the sun. Thus, it is in these villages of Mâcon where the richest and ripest Chardonnays in Burgundy are produced, filled with tropical fruit flavors and enhanced textures and flavors due to oak aging.

Alright, since the theme is Burgundy, I’ve got a little Burgundy wine review…

About the Wine: Louis Jadot 2016 Bourgogne Rouge (purchased at local Whole Foods market)

About the Wine: Louis Jadot 2016 Bourgogne Rouge (purchased at local Whole Foods market)

As you can tell from the label, and as discussed in my previous post about the Burgundian appellation hierarchy, this is a regional red wine made from Pinot Noir grapes sourced from all over Burgundy in general. (So no, this is no fancy village appellated wine, and certainly not one from a premier or grand cru.)

Flavor Profile:

Appearance: pale ruby

Aroma: Youthful, with medium aroma intensity: red cherry, wild strawberry, eucalyptus, cranberry, cedar, white pepper.

Palate: Dry with high acidity, medium tannins, medium alcohol, medium body, and a medium flavor intensity: strawberry, red cherry, white pepper, charred wood, cedar, dill, eucalyptus, cranberry. The wine has a medium-length finish.

Conclusion: Based on the WSET criteria, I would say that this is a Good wine that one should enjoy now. I don’t believe it has the best potential for aging—nothing on the nose nor the palate indicated or even hinted at tertiary flavors, which are the main clues when deciding this last factor. Some people may mark this wine as “simple,” and I could see the argument for that as well. However, my personal assessment is that the use of oak adds a bit more balance and complexity than I would expect from a wine marked “simple.”